With our increasing use of technology, is it necessary to teach handwriting in primary schools? Research suggests that the benefits of teaching handwriting go beyond simply writing (Dinehart, 2014). There is increasing evidence of a link between the fine motor skills required in handwriting and the development of cognitive skills which lay the foundation for later academic success. When children write letters, they demonstrate better letter recognition skills which means they learn to read quicker.

Research suggests that the process of forming letters while handwriting activates neural pathways that are associated with strong reading skills. In fact, handwriting plays a crucial role in the formation of these brain networks which underlie the development of strong reading skills. These brain connections are only made when children are engaged in handwriting activities, not when tracing or typing letters (James & Berninger, 2019).

Therefore, replacing handwriting instruction with keyboarding skills in the primary school years can be detrimental to students development of literacy skills. “Switching to keyboarding before students have developed handwriting skills may reduce their ability to recognise letters” (MacKenzie, 2019) which impacts their letter-writing fluency and overall reading development.

When children learn to write by hand, they not only learn to read more quickly, but they are better able to generate ideas and retain information. Berninger (cited in Konnikova, 2014) found when children wrote text by hand, they produced more words, more quickly than on the keyboard, but they also expressed more ideas.

Why teach handwriting?

Learning handwriting can be compared to learning times tables. Just as we know that in mathematics, a good automatic knowledge of the times tables can free up the brain for higher-order thinking, the same can be said for handwriting. If it is automatic, children can concentrate on the content of what they are writing instead of focusing on correct letter formation etc. This means they are better able to generate ideas and retain information.

For an early writer, their mind can be freed up to think of phonics, spelling, punctuation and the message they are trying to convey. If letter formation is laboured and cognitively difficult, the reverse is typically true; the students’ spelling is typically poor, their punctuation is lacking and the content of their writing can be disjointed or unclear or very brief, rather than lengthy and detailed.

We need children to have a good grasp of handwriting so that they can demonstrate an understanding of concepts taught. Ultimately, after emerging from an effective program to teach handwriting, students should be concentrating on idea formation not letter formation!

The evidence is overwhelming – effective handwriting instruction is an important part of literacy instruction and yet, there is insufficient direct handwriting instruction in many schools (Asher, 2006). The ultimate aim of handwriting instruction in schools is for the students to achieve legibility and speed. Like with other academic skills, the extent to which children are able to eventually write legibly and with speed depends on the development of foundational writing skills. In general, children’s handwriting is actually slower now because they are practicing less. Regular, explicit handwriting instruction in the classroom is CRUCIAL for effective development of this important skill. In conjunction with this, a CONSISTENT approach throughout a school is vital so that children have the best opportunity to master the complex task of handwriting.

How to teach handwriting?

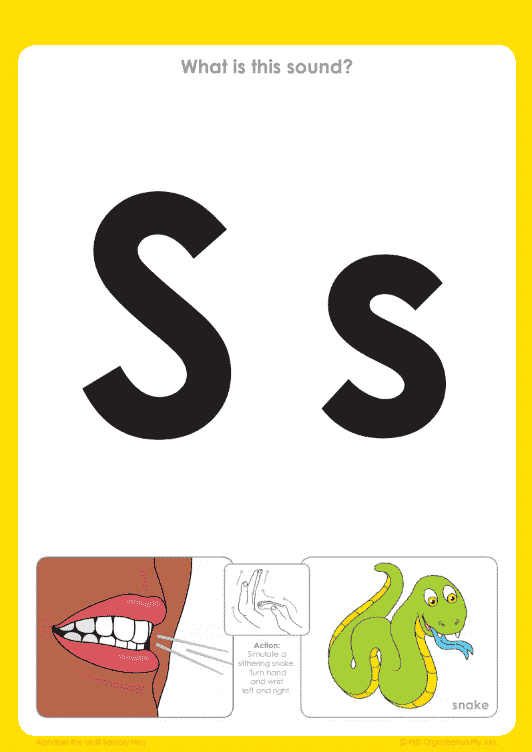

Letter formation activities should be a part of daily phonics instruction. As children hear the sound they develop strong auditory recognition; as they say the sound they develop strong pronunciation skills; as they see the sound/letter, they develop strong visual recognition skills; and as they write the sound/letter they develop strong letter formation skills. This holistic approach ensures children develop strong representations of the letters/sounds for both reading and spelling skill development.

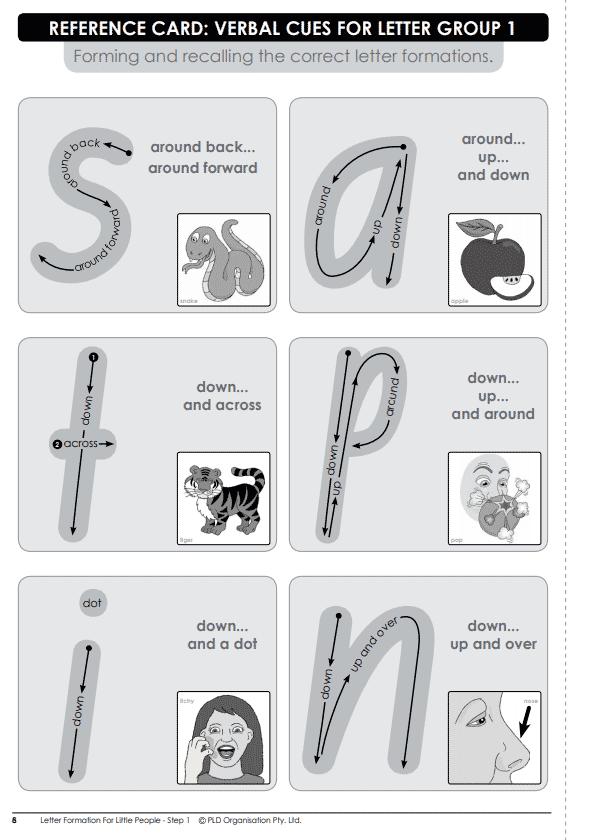

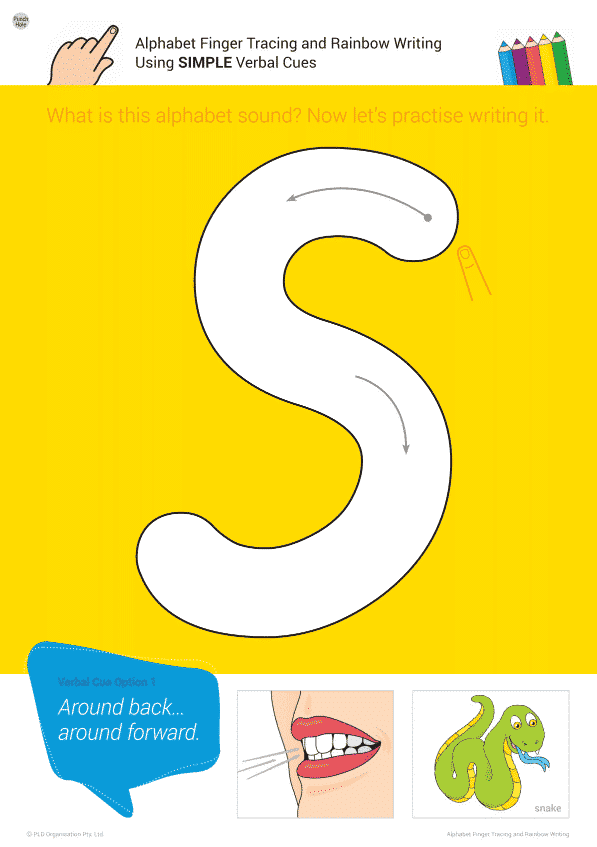

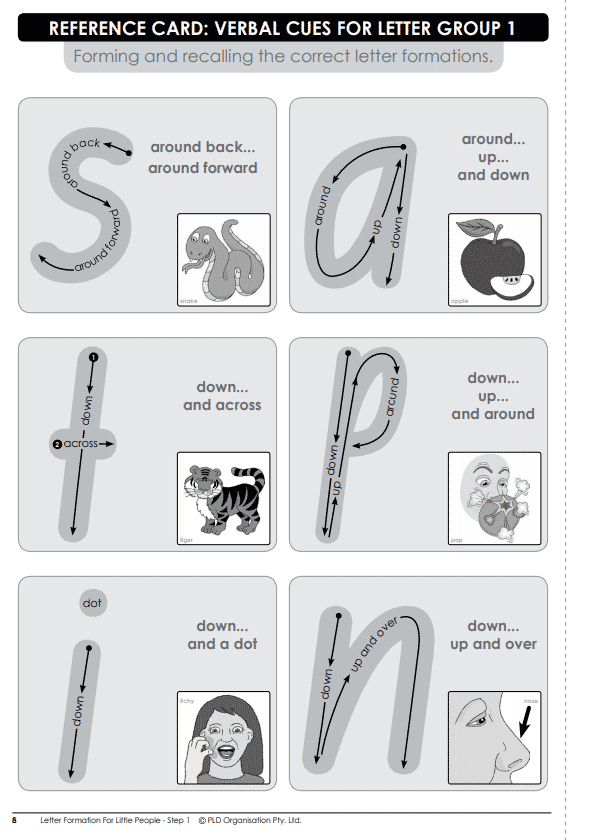

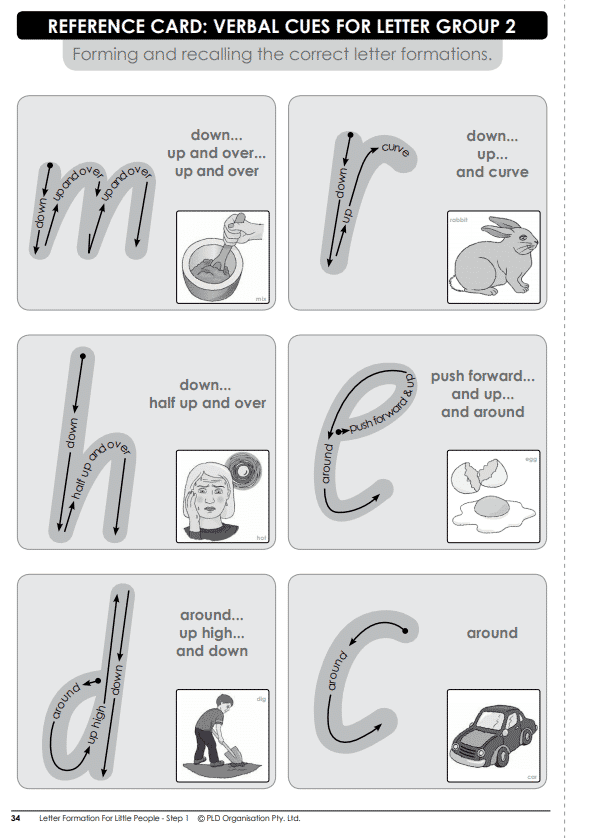

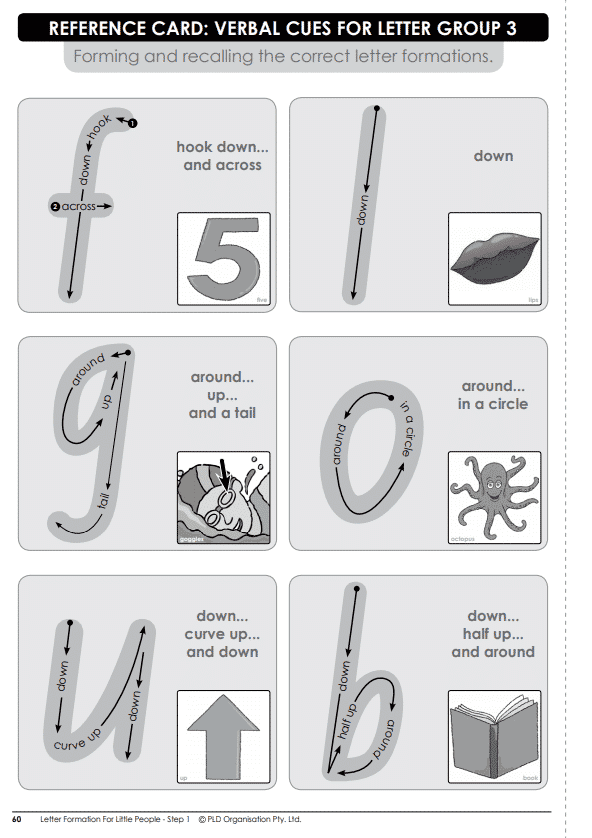

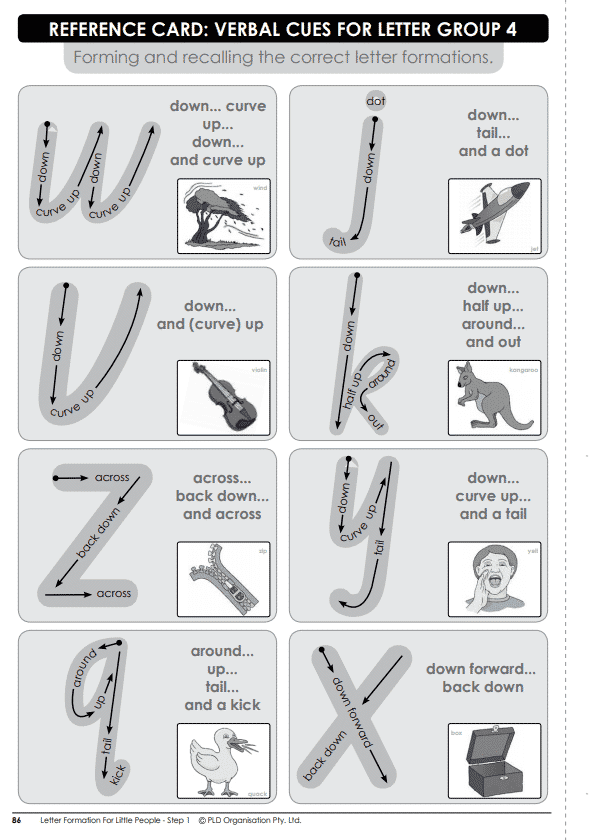

A multi-sensory approach (instruction and practice in a variety of different styles of learning) appears to have significant advantages in handwriting acquisition. Combining numbered arrows, starting points for letter formation and air writing has been found to be effective in assisting a child to develop consistent formation of letters. In the early years the focus is on the development of correct motor patterns, rather than on speed. This research forms the basis of PLD’s approach which provides visual prompts in the form of arrows, combined with verbal cues for letter formation and the practice of air writing to help consolidate strong letter formations.

The importance of a consistent approach

The importance lies in the CONSISTENCY of the approach a school uses towards handwriting. It is essential that from one year to the next, each teacher adopts a similar style of handwriting instruction, to allow for maximum retention by the students and effective incremental learning. The adoption of the PLD handwriting range over 2 to 3 years will assist in the facilitation of a consistent approach.

For example:

- Pre-Writing Patterns – in 3 to 4-year-old preschool programs

- Letter Formation for Little People – in the 4 to 5-year-old program

- Phonic Handwriting – in the 5 to 6-year-old program (currently being re-written by an Occupational Therapist)

The above sequence of programs could also be enhanced by the implementation of a wide range of fine and gross motor skill development within a 3 to 5-year-old program. PLD’s Preparing Children for Handwriting – Step 1 and Preparing Children for Handwriting – Step 2 were designed for this reason.

Handwriting instruction and dictation are central to a multisensory phonics program. PLD’s literacy approach also incorporates dictation through our Phonic Dictation range.

Existing handwriting booklets are often used in classrooms as independent work, risking the development of ‘bad’ habits in handwriting (such as reversals, incorrect or incomplete formations). Adequate teacher-led explicit letter formation rehearsal is vitally important in the early years to avoid the development of undesirable handwriting behaviours.

PLD recommends explicit teaching of letter formation as part of a synthetic phonics approach to literacy. By establishing an ideal handwriting technique and embedding this instruction within daily phonic instruction, each student’s potential for academic success will be maximised.

Cursive or foundation font?

Researcher Dr Virginia Berninger, suggests teaching print first as it transfers better to word recognition; then introducing cursive later (in the middle primary years) as it assists in the development of speed for compositions; and finally in the upper primary years the introduction of touch typing skills.

Adopting a cursive font for spelling and writing and a foundation font (found in the majority of readers) for reading, makes the process more complicated. This is especially true for children who have difficulty with visual perception, and forming a memory of the letter shapes.

Cursive letters are more difficult for students to recognise, and letter reversals are not reduced by using cursive fonts (Richmond, 2010). There is no evidence to support the theory that students transition to joined writing more easily when using a cursive font.

In the early childhood setting, teachers will come across difficulties when a cursive font is instructed.

Significant numbers of young children will experience difficulty with the ticks at the end of letters being formed. Some of these students will produce large or disproportionate ticks (i.e. poor control of the ticks). Other students may form a foundation font letter and then after the removal of the pencil a tick is then added (i.e. rather than a continuous and controlled single motion, 2 patterns are produced with a pencil lift between each.)

A consistent reading and handwriting font is recommended to enhance children’s handwriting and literacy acquisition. At PLD, our position is always to suggest a foundation font from the Early Years to Year 2 and thereafter a cursive font. We believe that this sequence gives students the best opportunity to establish confidence in literacy and fine motor skills allowing them to gradually develop speed and their own style.

For further discussion see the PLD blog post: Cursive versus Foundation Font: Deciding what font to teach.

In what order should letters be introduced?

The order of introduction of the letters of the alphabet to beginner writers appears to have no impact on the quality of their handwriting. However, as capitals are used less frequently, they are less essential in early instruction.

Ideally, the sequence in which letter formation is introduced should follow that of the Structured Synthetic Phonics (SSP) Program used. This holistic approach ensures children develop strong representations of the letters/sounds for both reading and spelling skill development.

In an SSP Program, reversible letters commonly confused are grouped and taught separately. This is also important for handwriting development as a child will make fewer errors when one letter formation has been well learned before a similar reversible letter is introduced (e.g. b/d).

PLD’s Structured Synthetic Phonics approach is based on the latest research and incorporates phonics instruction with writing instruction.

Featured in Letter Formation for Little People Step 1 (an Early Years Program), for the Foundation program see Letter Formation for Little People Step 2. For Year 1 program see Letter Formation for Little People Step 3

-

Letter Formation for Little People – Foundation Font – Step 1$82.50$82.50 incl. GST

-

Letter Formation for Little People – Foundation Font – Step 2$82.50$82.50 incl. GST

-

Letter Formation for Little People – Foundation Font – Step 3$82.50$82.50 incl. GST

In conclusion…

Considering the research evidence for the importance of handwriting instruction for literacy learning, the question of whether it is necessary to teach handwriting in this era of technology should be replaced with the question of “How can educators justify not teaching handwriting as well as computer tools during the elementary and middle school grades?” (James & Berninger, 2019, p.29).

PLD’s approach to literacy instruction is based on the latest research and incorporates structured synthetic phonics with handwriting instruction in addition to programs focusing on dictation and narrative development.

At PLD we believe handwriting instruction is critical to the development of writing AND overall literacy development as evidenced by our multi-sensory approach to literacy instruction.

References:

- Asher, A. V. (2006) Handwriting Instruction in Elementary Schools. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60, 461-471.

- Dinehart, L. H. (2014) Handwriting in Early Childhood Education: Current Research and Future Implications. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 0 (0), 1-22.

- James, K. & Berninger, V. (2019) Brain Research Shows Why Handwriting Should Be Taught in the Computer Age. LDA Bulletin, 51 (1), 25-30.

- Konnikova, M. (2014) What’s Lost as Handwriting Fades. The New York Times, 2 June 2014.

- MacKenzie, B. (2019) How to Teach Handwriting – and Why It Matters. George Lucas Educational Foundation. https://www.edutopia.org/article/how-to-teach-handwriting-and-why-it-matters

- Richmond, J. E. (2010). School-aged children: visual perception and reversal recognition of letters and numbers separately and in context. Doctor of Philosophy, Edith Cowan University, Perth.

print

print