One of the most common questions PLD receives is “Should students focus on a new book each day, or should students reread the same book several times?” This is a great question and one where research will be referenced to guide a response. Included also will be a summary of the evidence base for how to improve ‘Reading Fluency’ in a Foundation to Year 2 context.

What is Reading Fluency?

Reading Fluency is the ability to read with speed, accuracy, and expression. The average rates for reading age-appropriate material with few or no errors (Konza, 2011):

- By the end of Year 1: 60 words correct per minute.

- By the end Year 2: 90/100 words correct per minute. and

- In Years 3–6: 100–120 words correct per minute (with less than 3 errors and with the material getting progressively harder)

- Skilled adult readers: 180 words correct per minute.

What Influences a Student’s Rate of Reading Fluency?

The research tells us that reading comprehension and reading fluency are intricately linked and both are vital building blocks of a skilled reader. Reading Fluency is interconnected with word reading (or word recognition) and language comprehension. For students to read at an appropriate rate and with expression, research suggests that reading fluency relies on the ability to decode and comprehend at the same time. On the other hand, if students are not fluent readers, they need to use significant cognitive resources to decode, which leaves fewer cognitive resources for comprehension. Reduced skills in either area typically impact reading fluency.

Repeated Reading

For many years, repeated reading (RR) has been a widely adopted method for facilitating reading fluency. RR requires a student to read the same passage multiple times until an appropriate level of fluency is reached. From its meta-analysis, The National Reading Panel reported that guided repeated oral reading is a valuable fluency-enhancing task. The report stated “repeated reading…[which] have students reading passages orally multiple times while receiving guidance or feedback from peers, parents or teachers are effective…” (2000, p3). This report concluded that RR is likely to improve reading accuracy, reading fluency and reading comprehension. RR is particularly effective in the lower primary years and for struggling readers into the high school years.

Continuous Reading

Continuous reading (CR), also called wide reading, requires a student to read continuously for a specified time and each session utilises a different passage or reading book. When these two approaches are compared, RR and CR were found to have no real difference in terms of outcomes for students (Hempenstall, 2014). Current research suggests reading a text non-repetitively has the same positive effect on comprehension and fluency as RR. It is the quantity of targeted reading practice that is key.

“The act of simply reading connected text may be the mechanism that underlies fluency growth, and not repeatedly reading the connected text” (Hammerschmidt-Snidarich et al, 2018, p.645).

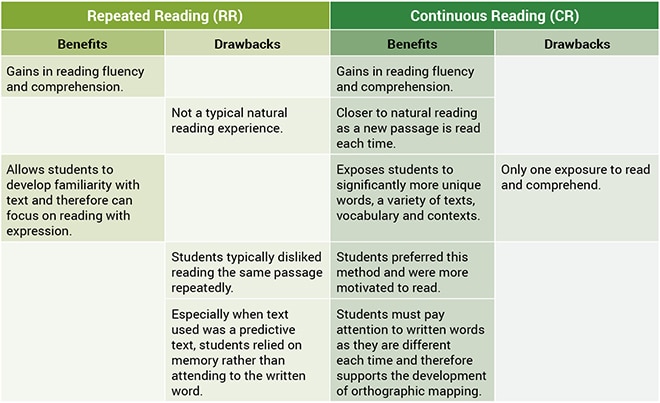

Since there is little difference between the outcomes of RR and CR, it is worth considering the potential benefits and drawbacks of each method:

When looking at this comparison between RR and CR, several considerations can be drawn. These include:

- RR has a role to play in the very early stages of literacy acquisition, as with each additional reading the student relies less on decoding and can practice reading with greater fluency at a whole word level.

- CR is reported to be more natural, motivating and enjoyable for students while exposing them to a wider range of vocabulary.

- CR supports the development of orthographic mapping. When a student re-reads a passage they tend to memorise words and rely on their memory without always attending to the words. However, when each reading session is a new text, students are forced to pay attention to the structure of words and cannot rely on memory. This develops a habit of attention to the phonemic and letter patterns of words which is critical to the development of orthographic mapping skills. As David Kilpatrick (2016) points out, without skilled orthographic mapping, exposure and repetition do not improve a student’s ability to retain new words in any substantial way.

- In our experience, RR does not appeal to many students. A typical comment from students being “I have already read that book!” PLD’s Phonic Dictation series aims to counteract this by adding a timed aspect to the readings. In our experience, we have found that it is motivating for students to observe that their re-readings become more accurate and fluent. To see how you can motivate students whilst improving their fluency, read our article Using the Phonic Dictation Passages For At-Home Decodable Reading Material.

Implications for Schools

The key factor in improving reading fluency is the amount of reading a student does. This relates to both the amount of time students spend reading and the amount of text they read. Therefore, for effective fluency instruction, educators need to provide opportunities for:

- regular practice

- reading aloud to an adult

- receiving corrective feedback on errors made

- reading an appropriate type of an evidenced-based reading book

What are Evidenced-Based Reading Books?

In the early literacy phase, texts should be brief (100-200 words) and at an age-appropriate level that allows for approximately 95% correct reading. Reading books should initially be decodable to support the student’s emerging phonic knowledge. As reading skills develop, the range of books students read should develop accordingly. For more information about how decodable reading books function within the PLD process, see this article.

What Can We Do if My School Has Limited Decodable Reading Books?

If your school has limited decodable reading books and mostly whole-language non-evidence-based readers, the precious and limited decodable books can still be sent home. The decodable readers will need to be read and re-read by students multiple times (up to four rereads).

For schools with adequate stock of decodable junior primary reading books, CR is likely to be the more suitable option (provided that the reading material is appropriate and matches the student’s phonic and decoding ability). PLD recommends the presentation of the Early Reading Screen located in the PLD Screening & Tracking Manuals to determine the type of reading material your students require.

The Importance of Immediate Feedback

When students are learning to read aloud, they must receive immediate feedback on any errors they make to ensure learning is maximised. Feedback has been identified in the research as critical to the development of reading fluency. For example, The National Reading Panel (2000) found repeated reading with feedback was superior to repeated reading alone. If a student is making too many mistakes, the reading material may be too hard.

The Importance of Oral Language Comprehension

Oral comprehension skills merit instruction as they will improve both reading fluency and reading comprehension. PLD recommends that in addition to sending home reading books, students are also provided with quality children’s picture books for parents to read to their child each night and ask targeted questions. Reading aloud to the child and asking appropriate questions is a powerful activity in supporting oral comprehension skills and vocabulary development. PLD’s Comprehension Questions range provides speech pathology scripted question cards matching a range of common picture books.

References

- Hempenstall, K. (2014). What works? Evidence-based practice in education is complex. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 19(2), 113-127.

- Hammerschmidt-Snidarich, S. M., Maki, K. E. & Adams, S. R. (2018). Evaluating the effects of repeated reading and continuous reading using a standardized dosage of words read. Psychol Schs, 56, Pages 635-651.

- Kilpatrick, D. A. (2016). Equipped for Reading Success. Casey & Kirsch Publishers, New York.

- Carver, R. P. (1990). Reading rate: A review of research and theory. Academic Press.

- The US National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read (2000)

print

print