Reading is a vital skill we use multiple times a day, often with minimal effort. However, this ability to read effortlessly, to understand different texts and read with pace, expression and fluency, is not a naturally developing milestone or innate ability.

It requires explicit instruction and rehearsal of many components, which are identified in educational papers, articles and research including The Reading Rope created by Dr. Hollis Scarborough (Scarborough, 2001), as well as in the Five Pillars of Reading – a result of the Report of the National Reading Panel (National Institute of Child Health and Development, 2000).

One of these key components, fluency, was specifically highlighted as a key contributor to reading development and has been the subject of renewed consideration by researchers.

What is Fluency?

Fluency is essentially a reader’s ability to read with little effort, minimal errors, speed and expression. A fluent reader can read as one speaks and comprehends what is being read without having to pause regularly to decode words. Research supports a strong correlation between fluency and comprehension, as cognitive energy can be used to concentrate on making meaning from a text, rather than reading. each. word. with. effort.

Components of Fluency

Every definition of fluency includes these three essential elements:

- Accuracy

- Speed or Reading Rate

- Expression / Intonation / Prosody

Accuracy and speed are often listed as the two most important factors- without these, one is unable to read with expression. Let’s look at these three foundational factors in a little more detail.

Accuracy

Research suggests that comprehension can be impaired if a reader reads less than 95% of a text accurately (Raisinski et al., 2011) and reading accuracy for early readers needs to be even higher at around 97-98%. Reading texts with success, especially for emerging readers, promotes positive experiences, reduced anxiety and increased confidence. Ensuring readers have access to texts at an appropriate level is important.

The acquisition of orthographic mapping skills enables readers to store and retrieve words automatically by sight. Although this is a gradual process, Ehri (2005) describes how sounding-out or decoding progresses to automatic recognition. These words become part of the mental dictionary or lexicon of words and, in turn, improve reading accuracy.

Rate

Reading rate refers to the speed at which a text is read. The rate at which words are decoded or read with automaticity, is an important aspect of fluency, however it is important to note that fast reading does not enable comprehension. Reading rate is measured using oral reading fluency (ORF), assessing words correct per minute, which is explored further on.

Expression/ Prosody

This final element is the key to bringing texts to life. Expression, also known as prosody, includes but is not limited to volume, pitch, tone, emphasis, stress and rhythm. Other related components involve the reader’s ability to use punctuation clues and phrasing. According to Wennerstrom, prosody is “the music of everyday speech” (2001). Prosody is commonly referred to as the third building block as, without speed and accuracy, reading with expression cannot occur.

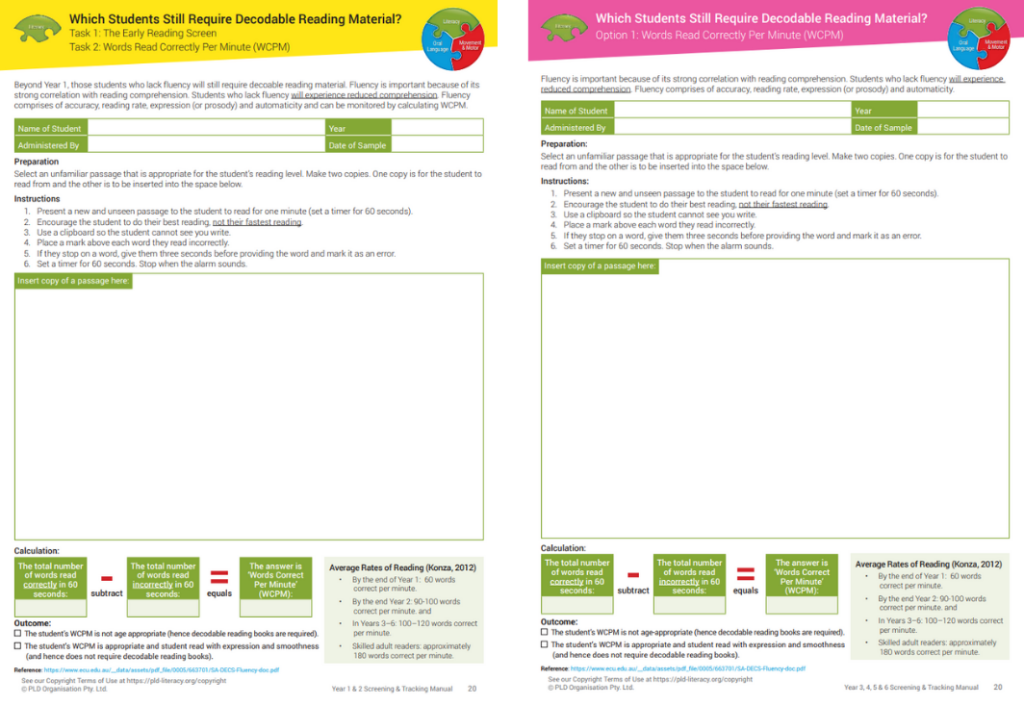

Assessing Fluency; Words Read Correctly Per Minute

Calculating and keeping record of children’s words correct per minute (WCPM) throughout the year can provide valuable information regarding reading progress in terms of accuracy and rate.

When calculating words correct per minute (WCPM), teachers need to:

- Present a new and unseen passage to the student to read for one minute.

- Encourage the student to do their best reading, not their fastest reading.

- Use the clipboard so the student cannot see you write.

- Place a mark above each word they read incorrectly.

- If they stop on a word, give them three seconds before providing the word and mark it as an error.

- Set a timer for 60 seconds. Stop when the alarm sounds.

Average Rates of Reading (Konza, 2012)

By the end of Year 1: 60 words correct per minute.

By the end of Year 2: 90 -100 words correct per minute.

In Years 3 – 6: 100 – 120 words correct per minute.

Skilled adults readers: approximately 180 words correct per minute

How to Develop Fluency

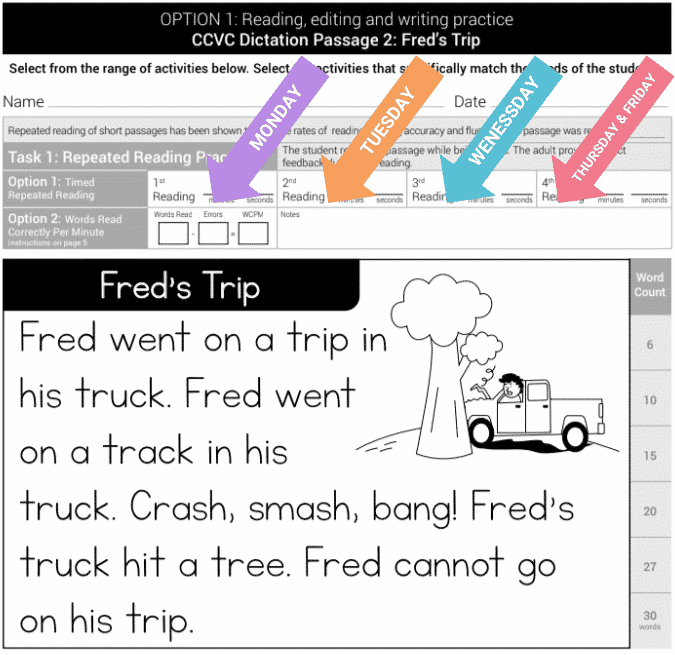

For many years, repeated reading (RR) has been a widely adopted method for facilitating reading fluency. RR requires a student to read the same passage multiple times until an appropriate level of fluency is reached. Continuous reading (CR), also called wide reading, requires a student to read continuously for a specified time and each session utilises a different passage or reading book.

You can read more about repeated and continuous reading here.

Some other activities to promote fluency include teacher modeling, choral and paired reading, using poetry, songs or Readers’ Theatre read alouds and read alongs with auditory devices.

Conclusion

As Konza (2011, pg.6) states so accurately, “The achievement of oral fluency marks an important point in a students’ reading journey. It reinforces the relationship between learning to read and reading to learn.”

Educators and parents have a deep responsibility to nurture all the elements of reading, including fluency as research tells us that literacy skills have a significant impact on an adult’s social participation, work opportunities, self-esteem and quality of life.

References

Hasbrouck, J., & Glaser, D. (2019). Reading fluency. New Rochelle, NY: Benchmark Education Company. https://www.benchmarkeducation.com/benchmarkeducation/y35121-reading-fluency-understand-25e2-2580-2593-assess-25e2-2580-2593-teach-professional-learni.html

Hasbrouck J & Tindal GA (2006) ‘Oral reading fluency norms: A valuable assessment tool for reading teachers’, The Reading Teacher, 59(7), pp.636–644, doi:10.1598/ RT.59.7.3

Hasbrouck, J. & Tindal, G. (2017). An update to compiled ORF norms (Technical Report No. 1702). Eugene, OR. Behavioral Research and Teaching, University of Oregon. https://www.readingrockets.org/sites/default/files/2017%20ORF%20NORMS.pdf

Konza

www.decs.sa.gov.au/literacy/files/ links/UtRP_1_5.pdf

https://www.ecu.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/663701/SA-DECS-Fluency-doc.pdf

Rasinski, T. V., Reutzel, C. R., Chard, D., & Linan-Thompson, S. (2011). Reading Fluency. In M. L. Kamil, P. D. Pearson, E. B. Moje, & P. P. Afflerbach (Eds.), Handbook of Reading Research (Vol. IV, pp. 286-319). New York: Routledge.

Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read (April 2000). National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and U.S. Department of Education.

https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=b0WdAAAAMAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=Five+Pillars+of+Reading+national+reading+panel&ots=RccFlmO08n&sig=x5g3ZKfWq-ACOOoSbXuRRQXzoZ8#v=onepage&q&f=false

Scarborough, H. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of Early Literacy. New York: Guilford Press.

https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=sfKpsYBGX2MC&oi=fnd&pg=PA23&dq=Scarborough,+H.+(2001).+Connecting+early+language+and+literacy+to+later+reading+(dis)abilities:+Evidence,+theory,+and+practice.+In+S.+B.+Neuman+%26+D.+K.+Dickinson+(Eds.),+Handbook+of+Early+Literacy.+New+York:+Guilford+Press.&ots=rzmIK7Daik&sig=mn8UMwduJz0v0MdaK8h2o8-Ubaw#v=onepage&q&f=false

Wennerstrom, A. (2001) The music of everyday speech : prosody and discourse analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

https://books.google.com.au/books/about/The_Music_of_Everyday_Speech.html?id=CFQSDAAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y

print

print