This article is for educators teaching older students that require decodable reading material beyond junior primary (or students who need to develop fluency).

In days gone by, decodable readers were depreciated for having dull plots and limited vocabulary; very unappealing for older students still requiring decodable reading material. In response, PLD sourced a range of catch-up decodable reading books that appeal to students aged between eight and fourteen that feature contemporary storylines and lively characters.

With explicit teaching of PLD’s Structured Synthetic Phonics (SSP) program, by the end of Year 2 most students will no longer require decodable readers. By this time, age-appropriate students should have the skills to decode most words independently and be ready to move on to general titles. However, every classroom presents with a wide range in ability that typically includes students in Years 3, 4, 5 & 6 working at a junior primary level, or presenting with low fluency. Consequently, these students still require decodable reading books.

Option 1: Determine if Older Students Require Decodable Reading Books

To set teaching goals and raise reading levels, it is essential to identify the locus at which a student is experiencing difficulty and target teaching from that point. PLD’s Early Reading Screen will identify this point, as well as:

- Determine and assign the correct level of decodable reading material.

- Track student progress.

We recommend administering the screen every term to students working within PLD Stages 1 & 2. For further details download the Year 3, 4, 5 & 6 Screening and Tracking Manual.

PLD has a range of high-quality decodable readers that match the SSP teaching sequence. Download the Decodable Reading Books Catalogue for the full range.

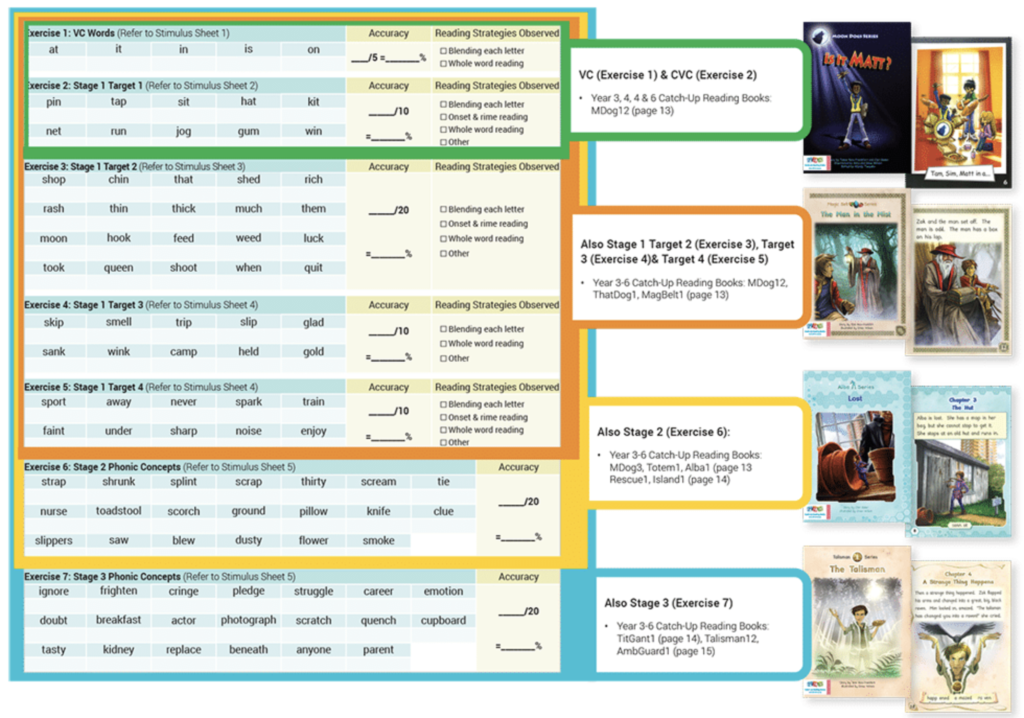

This is a snapshot of our Early Reading Screen and the associated ranges aligned with each exercise.

Option 2: Assess Fluency to Determine if Students Require Decodable Reading Books

Fluency has three core components; accuracy, rate and prosody. Fluency is important because of its strong correlation with reading comprehension (Allington, 1983). Students who lack fluency will struggle with comprehension. Since this is the ultimate goal of reading, it is crucial that teachers explicitly target this often neglected component of reading instruction.

Average rates of reading in the primary years (Konza, 2012):

- By the end of Year 1: 60 words correct per minute.

- By the end Year 2: 90/100 words correct per minute. and

- In Years 3–6: 100–120 words correct per minute.

- Skilled adult readers: 180 words correct per minute.

The rate required for basic comprehension is around 90-100 words per minute (typically achieved by the end of Year 2).

Along with PLD’s other screening and tracking tools, teachers should regularly assess fluency throughout the year to provide a clear record of reading progress in terms of accuracy and rate.

How to Calculate Words Correct Per Minute (WCPM)

- Select a list of words or an unfamiliar passage that is appropriate for the student’s reading level. A validated assessment can be used; make two copies.

- Present the passage to the student to read for one minute (set a timer). Encourage the student to do their best reading, not their fastest reading.

- Using a clipboard so the student cannot see your marking, place a mark above each word they read incorrectly. (If they stop on a word, give them three seconds before providing the word and mark it as an error).

- Count the total number of words read correctly.

- Count the total number of incorrect words.

- .Subtract the number of errors from the number of words. The answer is the average number of WCPM.

Example: If the student read 63 words and made seven errors within one minute, they had 56WCPM.

If you are administering a start of year (baseline) fluency screen, repeat the steps with another dictation passage and average the number of words read incorrectly and correctly to get an average number of WCPM. If is it just a termly check-in then one passage is sufficient.

We recommend recording achievement scores in a tracking sheet to monitor progress.

Students who score in the lowest 20-25% of the cohort are candidates for intervention. Teachers are able to determine the root of fluency difficulties by analysing the Early Reading Screen scores along with the student’s WCPM. Should low fluency be a result of decoding difficulties, targeted teaching and learning tasks to develop automaticity should be a focus (i.e. decoding, blending, word attack tasks). If low fluency is due to reading rate, interventions to develop this should be implemented (i.e. repeated reading).

Tier 2 students who are receiving evidence-based intervention need to be assessed on a more regular basis than their age-appropriate peers. PLD recommends at least twice per term (middle and end) but it can be done as often as each week. If students are not making progress after a semester of RTI they may need to be referred to a specialist. If you are following PLD’s programs and are unsure of whether to refer or how to refer, then please contact the office or Live Chat function on the website for guidance.

Prosody

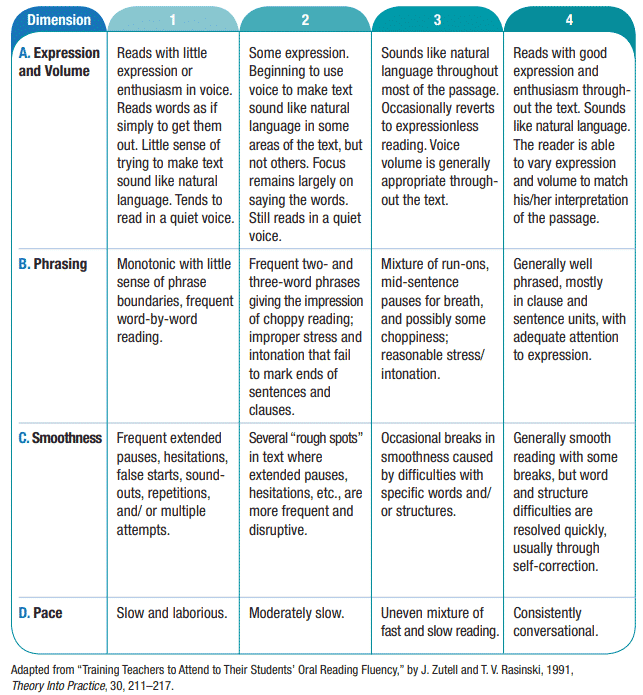

Expression is difficult to quantify; PLD suggests using checklists or rubrics to assess this component of fluency such as the one below.

Regardless of age, if students have not consolidated early reading skills or acquired adequate fluency, they continue to require regular and consistent rehearsal of letter-sound correspondence and blending through decodable readers.

Further Reading

- Two Evidence-Based Strategies to Improve Reading Fluency

- Why Decodable Reading Books Are Superior to Whole-Language Books When Learning to Read

- How Do Decodable Reading Books Function Within the PLD Process?

References

- Cheatham, J.P., Allor, J.H. The influence of decodability in early reading text on reading achievement: a review of the evidence. Read Writ 25, 2223–2246 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-011-9355-2

- Fisher, D., Frey, N. & Hattie, J. (2017). Teaching Literacy in the Visible Learning Classroom. Corwin Literacy: California.

- Konza, D. (2012). Research into practice: Fluency. Accessed at https://cer.schools.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/doe/sws/schools/c/cer/localcontent/konza_fluencypdf.pdf

- Mesmer, H. A. (2000). Decodable text: A review of what we know. Reading Research and Instruction, 40(2), 121-141. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388070109558338

print

print